Dedicated to Richard Ells and Bryan Roth

I. Why Am I Here At Gettysburg?

Wandering alone among the epitaphs carved in stone at this final resting place dedicated by Lincoln seven score years ago, I wonder to the meaning of the urge that brought me to this hallowed ground where brave men fought to define a nation.

The gray-black granite rock, scattered forlornly among rolling hills and clumps of spine-thin trees, dominate the countryside at Gettysburg, like solitary sentinels guarding row on row of ash-gray headstones of the dead.

It’s as though this sparse land cursed for lack of growth was ushered in on cue, a perfect desolate setting for the bloody battle between American brothers—the iron hinge on which the war swung to the Union.

Three days the fateful battle raged. Three days the destiny of our nation was in doubt.

The battle was won by the men in blue on the first day. The war was lost by the men in gray on the last.

II. The High Ground

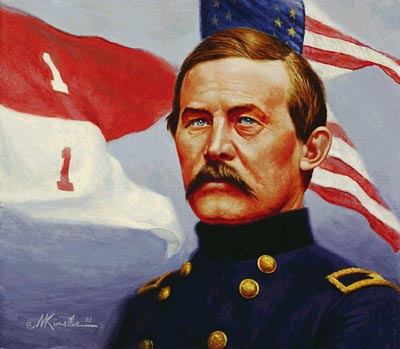

Rising ridges of rock stand like watchtowers south of Gettysburg. On the evening of June 30th 1863, Brigadier General John Buford turned in his saddle, looked upon those formidable battlements and chose to give blood before giving up the high ground.

Buford, with three brigades of 1,250 cavalry, was trained to use horses and men like American Indians – ride hard, dig in, shoot sure, and ride out fast. On July 1st, his horsemen slowed down the Confederate infantry.

John Buford

On July 2nd, 75,000 Confederates down from the north and 95,000 Union soldiers up from the south, converged in Adams County at the small town of Gettysburg, to fight the bloodiest of all battles to soak American soil.

The two armies were fixed in their historical roles: the South, the aggressor, fighting for its rights; the North, the reluctant combatant, was firmly entrenched on the high ground.

Because of Buford, the northern troops, guns and cavalry were well entrenched and fortified behind the rock ridges. Though they attempted to engage the southern troops below, repeatedly they were defeated and forced to retreat to the hills.

Looking at those hills, General Robert E. Lee was well aware any major battle put his gallant troops at a great disadvantage. But he also knew that if he could defeat the Army of the Potomac, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington were virtually unprotected.

Robert E. Lee

Lee, always opportunistic, had sought to invade the North because he knew the South could never win an extended war. The only hope was to bring death and destruction to northern soil and embolden those in the north who sought peace at any price.

The war was lost on July 3rd, when General Robert E. Lee ordered Major General George Pickett and nine brigades of 12,500 screaming Rebs to attack almost a mile over open field and then a half mile up to the rock ridges where 6,000 Yankees aimed for their eyes.

Lined up in double and triple ranks—a mile, flank to flank—brave Rebs marched, then double-timed, and finally ran uphill as on each flank a maelstrom of cannon fire cut them and a deadly hail of Minié balls sought out their heads.

The battle that saved this Union ended on Independence Day. God leaves signs for those who seek God’s providential hand. To the unbelieving, God’s intervention appears on the tablets of time as mere happenstance.

II. One Nation Under God

As I walk along the high ground on Cemetery Ridge, looking down to sparse of trees in the field below where Lee exhorted his brave boys to battle until they died, I am strangely encouraged, even assured.

I suspect talented and great men like Lee, with skill that charm and leadership give,

will make similar foolhardy decisions when they attempt to destroy a nation foreordained by God.

A nation conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all us–women and men–are created equal before God and consecrated by those who willingly gave their lives that this nation would have a new birth of freedom.

In his second inaugural address, Lincoln sadly reminisced that, though neither North nor South sought Civil War, the South made war rather than allow the nation to live while the North accepted war that the nation might not perish.

Abraham Lincoln

Suddenly, I am reminded of God speaking to another rebel nation: “Because your insolence has reached my ears, I will put my hook in your nose and my bit in your mouth and I will turn you back on the way by which you came.”

Early in the war, Lincoln wondered if at the heart of all republics there was an inborn weakness that soon cuts off their life’s blood—too strong, the republic hinders the liberties of the people; too weak, the republic will not be strong enough to endure.

Four months after the Battle of Gettysburg, as the Soldiers’ Cemetery was dedicated among the graves of some six hundred sixty-six dead for both North and South,

Lincoln knew why this nation, once reunified, would live.

Standing before gravestones flat to the ground, arranged in neat arcs of concentric circles, Lincoln proclaimed to a hushed crowd that this nation, would have a new birth of freedom, under God.

On a hot, sticky day after an evening’s dampening rain, our president, tall and gaunt in mournful black, declared the brave men living and dead would be consecrated forever,

that this government of the people would be free under God’s reign.

III. A New Civil War

Walking under knotty sycamore maples planted years after Lincoln redefined our nation, I find hundreds of headstones bear no names at all, unknown except to a caring God.

Suddenly, I think know why God has brought me here. Our nation again is in midst of a war that divides us – a war that tears apart families, sisters from sisters and brothers,

a war that divides us into competing camps.

Lincoln sought union above all at first. Only later in the war he began to understand

a nation set apart and defined by God could not be half free and half slave.

Lincoln came to understand that slavery is an offense to God, and in God’s own time, had to end. In his second inaugural address, Lincoln prayed the war might end, but acknowledged blood taken might need to balance blood given.

IV. The Rights of God

Alongside the graves of those who died at Gettysburg are headstones of soldiers whose lives were given in other wars. Like choirs to the lead singers at center stage,

they remind us that freedom is a battle without end. Walking among these upright stones, I think I hear moans, moans crying out against the blood of dead yanked unwillingly from wombs of hope. Precious blood spilled on our consecrated soil.

I see a soldier clad in blue cradling a baby in his hands. Another soldier in gray stands with a baby held high. Suddenly the cemetery is filled with soldiers dressed in olive drab, khaki brown and camouflaged green.

The soldiers’ moans become louder, filling the cemetery. I bang my hands to my ears to hide from the sounds, but then graves, flush against the ground, sing out, “Let our deaths not be in vain. Let our deaths not be in vain.”

I close my eyes tight to the cry of pain but strangely see a tall leader, gaunt-faced, framed in a beard, strangely white. Abraham, the president, father of many, stands before these graves of valiant dead and shouts:

“Look among the nations and see, wonder and be astounded, their justice and dignity proceed from themselves. They are grass, short-lived and soon dying. Seeing no further than themselves, they live no longer than themselves.”

Just as suddenly, this, this vision is gone and all is quiet. The night has quickly come, the orange glow on the horizon reflects warmly on each headstone, basking them in light,

comforting them against the onslaught of the night.

I know and you know why God brought me here. Like Lincoln, many of us put union above all else, thinking our republic protects women’s right to give or deny life and cover up our ears to thousands of embryonic cries.

As we came to know no one has the right to enslave, we must come to know that no one owns another’s life. The mystery that gives life to a child is God’s alone. God alone has the right to take life of the unborn.

In dedicating this hallowed ground that rainy morn, Lincoln challenged us then and forever to highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain – that this nation,

under God, shall have a new birth of freedom – and that the government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth.

Brave men who fought and died will not have died in vain if we here dedicate ourselves to the task now before us: all conceived on our country’s hallowed ground shall be afforded the right to life.

Stanford Erickson is a thirty-five year member of the National Press Club in Washington, DC, and a former member of the Overseas Press Club in New York City. For more than twenty-five years, as a Bureau Chief in Washington, DC, and a reporter and editor in New York City, he covered Presidents, Congress, Administrative and Regulatory Departments and Agencies. He has interviewed Presidents and other world leaders and many significant business leaders in the country. He lives in Vero Beach, Florida.

TRUMP-PENCE 2016

Veterans for TRUMP-PENCE

LikeLike